Nearly every one of the mine shafts plummeting below Bendigo have disappeared from people's memories, a local historian says. As TOM O'CALLAGHAN discovers, there is a forgotten world beneath your feet.

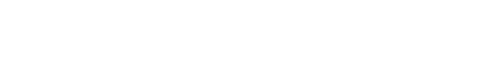

The bricks James Lerk is sitting on are choked by climbing weeds, which are ever-so-slowly smothering more of these forgotten foundations.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

Not all that long ago, in the grand scheme of things, these Bendigo ruins carried an air compressor used to drill into rock and are barely visible.

This mine belched out so much mullock that land in nearby King Street and Queen Street rose four feet.

Then, the Breen Street mine closed and the slow process of forgetting began.

Train passengers who now pass the site by metres could now be forgiven for not noticing one of the deepest mine shafts on the Bendigo gold fields.

Victoria is in the middle of a mining boom, with exploration licences being snapped up as companies harness modern technology to reexamine old ground.

Fosterville mine owners Kirkland Lake Gold's geosurveying helicopters have been spotted flying around Epsom and Huntly in recent months, Chalice Gold Mines is in the midst of a drilling exploration program west of Bendigo and Kalamazoo Resources this week revealed it hoped to expand searches south of Maldon.

The push to lock in exploration licences had been fueled by Kirkland Lake Gold "hitting the mother lode" at Fosterville, Kalamazoo Resources exploration manager Luke Mortimer said this week.

Kirkland Lake Gold this year upped its estimates of the amount of gold under Fosterville to $5 billion and Mr Mortimer said it was now arguably one of the most valuable mines in the world.

Even as the new gold rush took off, Mr Lerk said many people did not appreciate the scale of mining in Bendigo's past.

About 6000 mine shafts were sunk on the Bendigo goldfield and many people live, work and travel past them every day. They just don't realise it.

They had lost a connection to mines earlier residents had forged.

"(That's particularly the case for) younger people," Mr Lerk said.

"They would not have known that there was an immense amount of mining activity here, and that that's the only reason the city came into being in the first place.

"I think a bit more could be made of our mining history, so people know its social consequences, it's economic impact and the devastation it could also cause as far as the landscape was concerned."

Nearly all of Bendigo's shafts were sunk along a band just 4km wide, which stretched 18km from the far side of Spring Gully out to Eaglehawk.

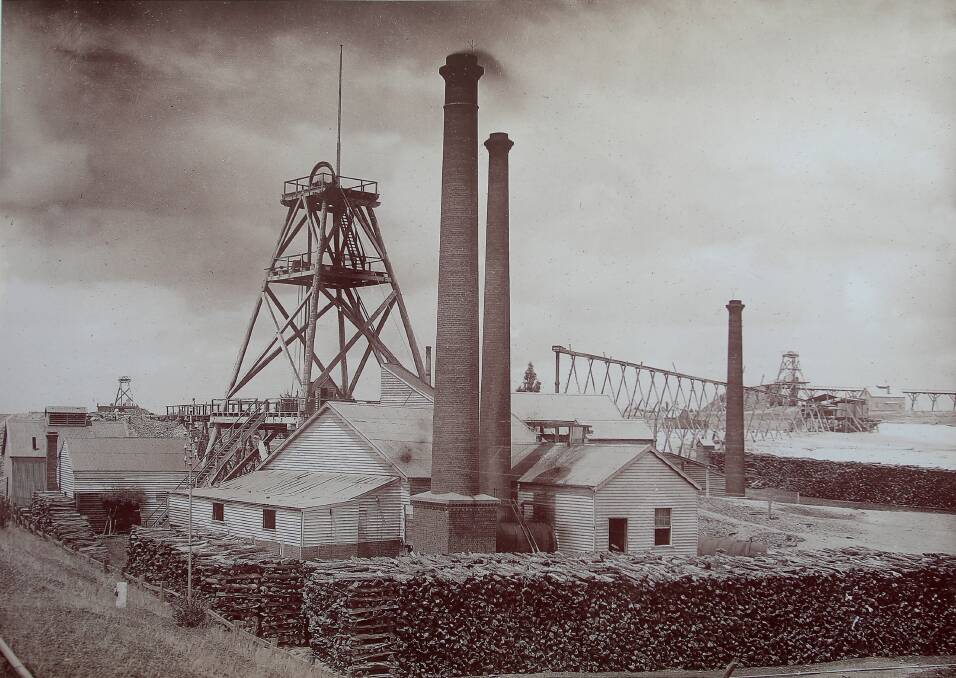

The Breen Street ruins are some of the more obvious remnants of mining activity, but others literally drop into the collective conscious every so often.

Properties had been known to sink in Bendigo.

"People would build a house in the 1930s or 40s. Later on they would find their driveway had disappeared or their backyard had fallen in," Mr Lerk said.

"They weren't aware there used to be a mine there."

The problem was not that shafts had not been well mapped.

"If, like here (at the Breen Street mine), the site has been obliterated you didn't know what you were building on," Mr Lerk said.

"Some mines were only covered over with timber, which would rot. So if dirt got over the top of that, with one thing or another, people would be unaware."

One opened up as recently as 2015 under an Ironbark bathroom, causing it to sink, and local historian John Kelly had collected newspaper clippings about others that had opened throughout the 20th century.

One undated Bendigo Advertiser clipping he found noted baseball players would have the "rare chance to hit a hole-in-one" during matches at Albert Roy Reserve in Eaglehawk after the cap caved in nearby."If you go up to the Marketplace there used to be a mine virtually underneath the vacuum cleaner shop," Mr Lerk said.

"Before that area was developed the old cap was removed. They excavated well-down and put a solid, big cap in."

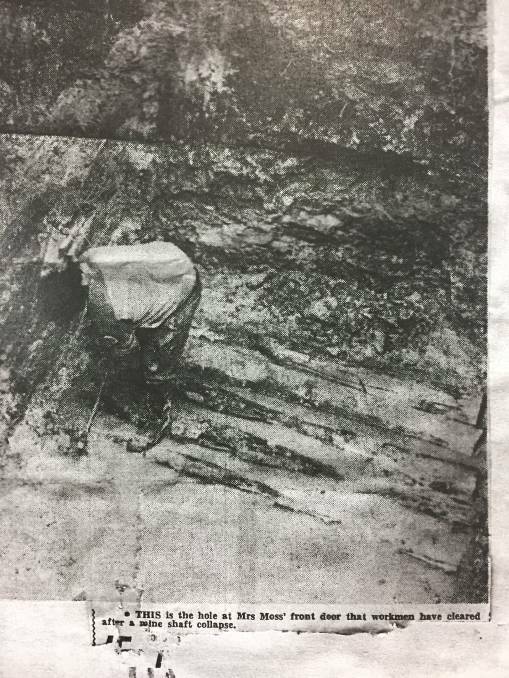

The history of mining in Bendigo was a bloody one and Breen Street's forgotten mine was responsible for a litany of deaths.

John Hardy, was killed at 55-years-of-age by explosives that he had packed into bore holes moments before. That happened in 1884.

John Hewitt heard a crack above his head and jumped the wrong way. A stone landed on his head. That was in December 1893.

Others were killed in the years until the mine closed. One was hit by machinery, two died after an explosion one kilometre underground and another plummeted to his death.

many more died more slowly. The great depth of the mine shaft, high temperatures and poor ventilation fueled tuberculosis and miners' phthisis.

Creating a successful mine took a certain amount of luck. The New Chum Railway mine, as the Breen Street operation was known, only ever produced 3.46 tonnes of gold.

"That's not a lot, really, when you consider its depth," Mr Lerk said.

The shaft was one of the deepest at 1,316 metres.

It's owner, WDC Denovan thought so little of his small mining claim that at one point he gave away shares to his friends.

He came to believe the mine was a lemon as miners dug through more and more dead ground, Mr Lerk said.

Then the mine hit gold and some of the shares he had given away rocketed to $20,000 in value.

The New Chum Railway mine closed in 1910. By 1954, the last of Bendigo's mines had shut, marking the end of 103 years of digging.

Yet, even as more shafts were abandoned people with "gold in their veins" never stopped searching for the next reef of rock, Mr Lerk said.

Many abandoned mines remained uncapped until the 1930s and even as they steadily filled with water people climbed into their depths.

"During the Great Depression there were quite a number of guys who went down to the water level of different mines in order to see what had been left behind," Mr Lerk said.

The Yates brothers went down the Kentish Mine north of Ironbark Creek, and found a gold-bearing quartz reef no-one had ever touched.

"People were desperate for work and getting another meal on the table," Mr Lerk said.

"The Yates brothers did quite well, but there are hundreds of people who lived on less than the smell of an oily rag.

"Mining is a bit like gambling. You have losers - most people are losers - and a few winners."

More history: Why 23 trams cost just $1 in 1977

The Yates brothers' trick was to ask former miners about mine shafts, something that could not happen today.

In the modern era, companies wanted to erase that gamble, hoping intensive surveys, rock sampling and other research methods will stop them losing money.

Mr Lerk wished he could have been there when early miners threw their dice.

"You'd like to be here at the start, like when this place (the New Chum Railway mine) was pegged out, for example, knowing what this place was going to deliver in share values, to get in on the ground floor," Mr Lerk said.

Have you signed up to the Bendigo Advertiser's daily newsletter and breaking news emails? You can register below and make sure you are up to date with everything that's happening in central Victoria.